by Steven Feldstein August 19, 2020

By late July, most rich countries had brought their covid-19 infection rates down far below their initial peaks. In the US, however, the number of daily new cases was at record highs and still climbing.

The crisis has badly damaged global opinion about American competence. A report in June from survey company Dalia Research revealed a broad consensus that China has handled covid-19 far better than the US. Of the 53 countries surveyed, ranging from Denmark to Iran, only two thought the US had responded better than China: Japan and the US itself. The Dalia survey also found that across the board, public perceptions of US global influence have markedly deteriorated. Nearly as many people believe that America’s impact on democracy has been negative as positive. People in stalwart democracies such as Canada, Germany, and the UK are particularly critical.

America’s abject failure to deal adequately with the biggest global health emergency in a century has prompted some experts to argue that the pandemic may serve as a geopolitical inflection point. Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi wrote in March in Foreign Affairs that just as a bungled intervention in the Suez crisis precipitated the end of the British empire, “the coronavirus pandemic could mark a ‘Suez moment’” for the US, as China “position[s] itself as the global leader in pandemic response.”

But even if the effects are not quite that drastic, they will be profound. The US’s declining stature in the wake of the pandemic is accelerating two global political trends that have emerged in the last five years.

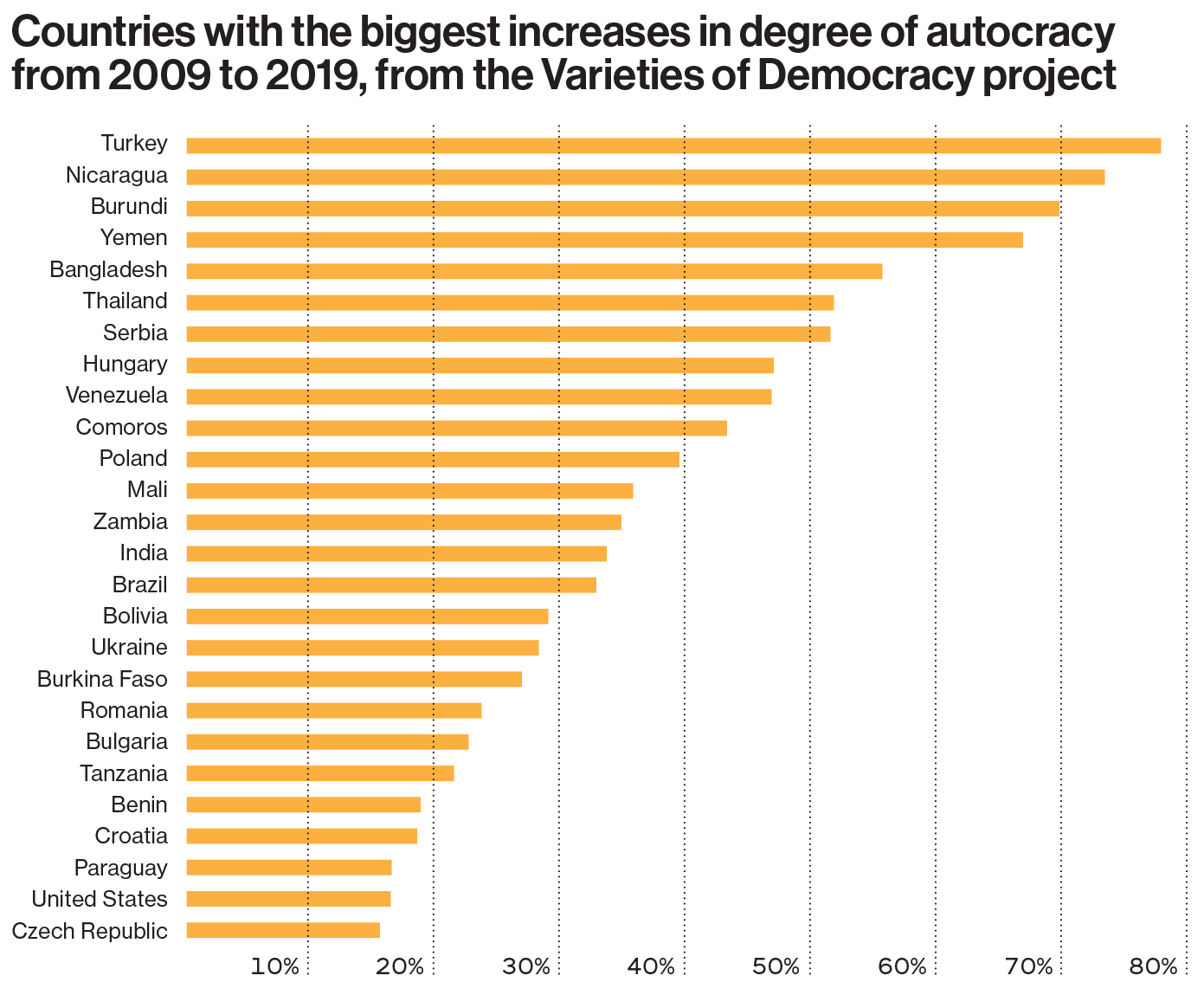

First, rising tensions between the US and China threaten to initiate a new arms race and a return of great-power rivalry. Second, from Turkey to Brazil to Hungary to Poland, an increasing number of countries are undergoing “autocratization,” centralizing power and restricting political freedoms—putting an end to the post–Cold War waves of democratization that ushered in new freedoms and rights for hundreds of millions of people. Taken together, these two trends will make for a more divided and uncertain world.

By late July, most rich countries had brought their covid-19 infection rates down far below their initial peaks. In the US, however, the number of daily new cases was at record highs and still climbing.

The crisis has badly damaged global opinion about American competence. A report in June from survey company Dalia Research revealed a broad consensus that China has handled covid-19 far better than the US. Of the 53 countries surveyed, ranging from Denmark to Iran, only two thought the US had responded better than China: Japan and the US itself. The Dalia survey also found that across the board, public perceptions of US global influence have markedly deteriorated. Nearly as many people believe that America’s impact on democracy has been negative as positive. People in stalwart democracies such as Canada, Germany, and the UK are particularly critical.

America’s abject failure to deal adequately with the biggest global health emergency in a century has prompted some experts to argue that the pandemic may serve as a geopolitical inflection point. Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi wrote in March in Foreign Affairs that just as a bungled intervention in the Suez crisis precipitated the end of the British empire, “the coronavirus pandemic could mark a ‘Suez moment’” for the US, as China “position[s] itself as the global leader in pandemic response.”

But even if the effects are not quite that drastic, they will be profound. The US’s declining stature in the wake of the pandemic is accelerating two global political trends that have emerged in the last five years.

First, rising tensions between the US and China threaten to initiate a new arms race and a return of great-power rivalry. Second, from Turkey to Brazil to Hungary to Poland, an increasing number of countries are undergoing “autocratization,” centralizing power and restricting political freedoms—putting an end to the post–Cold War waves of democratization that ushered in new freedoms and rights for hundreds of millions of people. Taken together, these two trends will make for a more divided and uncertain world.

A global digital divide

One visible manifestation of both the decline of US power and the resurgence of autocracy is the fragmenting of the global digital ecosystem. Since Google pulled out of China in 2010 over the government’s censorship of search results, China has cultivated a walled garden of applications primarily for use by its citizens. While the decoupling isn’t total—the Android and iOS mobile operating systems are prevalent, and programming languages like Java and Python are widely used—most Chinese never go on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Amazon, PayPal, or many other platforms, but instead use their local alternatives.

This fragmentation is part of a larger normative battle. China has been joined by Russia, Iran, and other autocratic regimes in promoting cyber sovereignty—the idea that countries should set their own rules on how their citizens use the internet. In Russia, the government is planning to implement a “sovereign internet,” a self-contained, centrally controlled system that would allow the country to cut itself off from the global internet entirely (see “Yandex’s balancing act,” page 38). By contrast, while the US and Europe differ on the nature and importance of privacy, the limits of free speech, and the right way to regulate Big Tech, there is broad agreement that the internet should be open and interoperable.

These trends mean that increasingly, where large countries relied on size, military force, or economic influence, they now also view technology (and not just the military kind) as one of the keys to sustaining and extending their power. This paradigm, known as “technonationalism,” rests on two crucial assumptions: first, that an early technological lead gives countries a first-mover advantage, and second, that dominance in certain technologies, such as artificial intelligence, gives them an edge in other fields. These assumptions do not need to be true to be influential. Under their logic, no country can afford to let competitors pull ahead.

An illustration of this was the US Commerce Department’s decision in October 2019 to add 28 Chinese companies to its “entity list” of firms subject to trade restrictions. They include most of the leading Chinese AI firms, including iFlytek, SenseTime, and Megvii. Ostensibly, they were added as punishment for facilitating shocking human rights abuses against Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang. But a secondary result was to hinder them from competing with US companies.

More recently, in May 2020, the White House released a strategy document accusing Chinese authorities of exploiting “the free and open rules-based order” and attempting to “reshape the international system in its favor.” It calls for renewed prosecutions of Chinese trade-secret theft and a stronger process for preventing Chinese companies from acquiring advanced technologies, such as “hypersonics, quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology.” Subsequently, US officials tightened restrictions against Chinese electronics giant Huawei by blocking the company from using US technology or machinery to manufacture its chips. In late July, the Trump administration abruptly ordered China to close its consulate in Houston, alleging that it was a hub for industrial espionage. China retaliated by closing the US consulate in Chengdu.

China, meanwhile, continues to lock out international companies that refuse to play by its rules—such as agreeing to censor search engine results, provide authorities with data on users, or hand over software source code and other proprietary data. It has also ramped up efforts to cultivate “mass innovation” and increase subsidies to strategic sectors such as AI, semiconductor chips, and aerospace through programs like “Made in China 2025.”

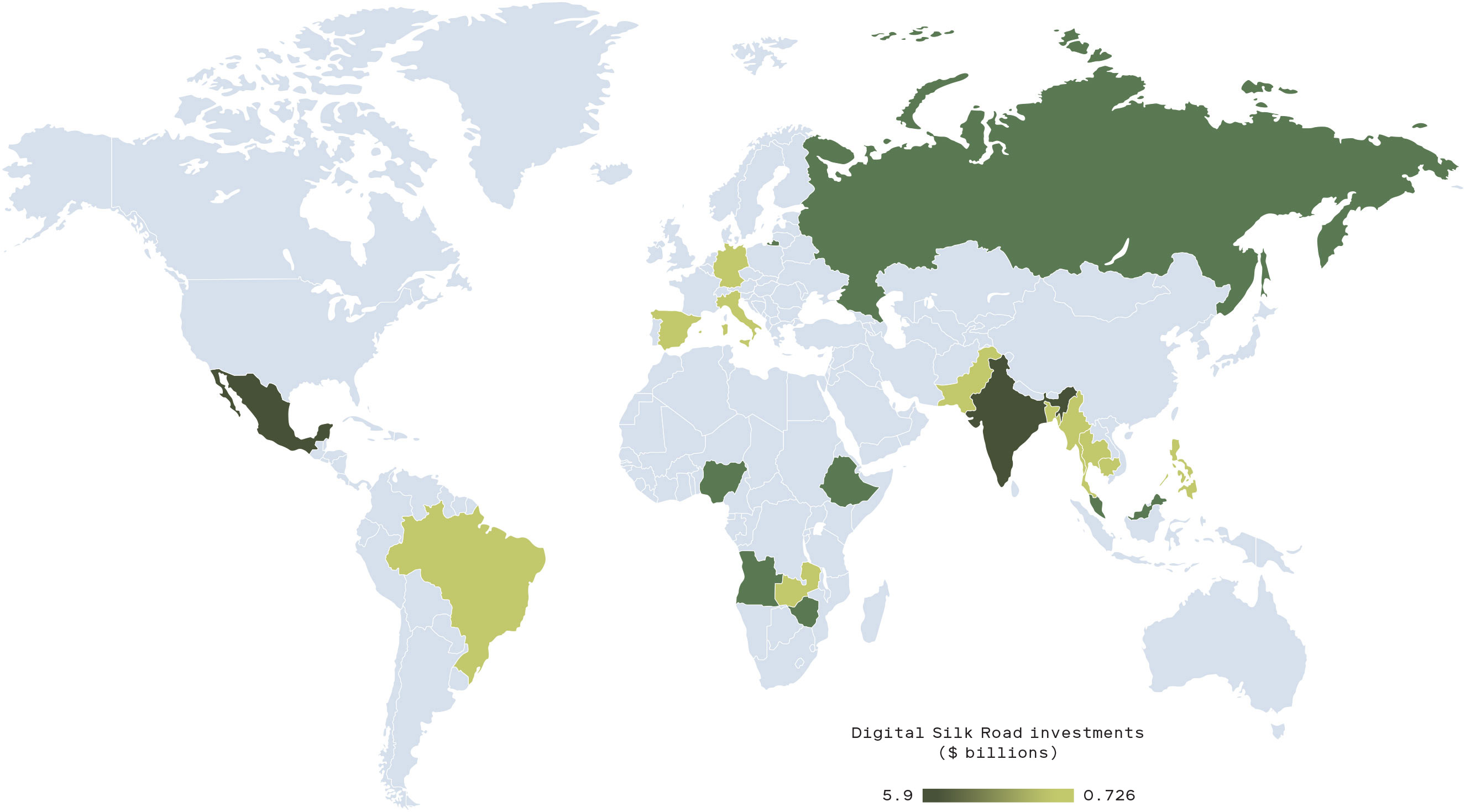

China also promotes its companies and technologies to many countries in direct competition with US, European, and other firms. Beginning in 2015, Chinese officials began touting the “Digital Silk Road,” focused on internet connectivity, artificial intelligence, the digital economy, telecommunications, smart cities, and cloud computing. This has led to investments in at least 20 countries, totaling nearly $40 billion, according to a 2019 estimate by the RWR Advisory Group, a consultancy.

Countries with investments from China’s Digital Silk Road

Source: Bloomberg

The Trump administration’s attempts to disentangle US technology supply chains from China and its moratorium on new visas for skilled foreign workers, announced in June and extended through December, only serve to help China. A report by Ishan Banerjee and Matt Sheehan published by the Paulson Institute, a think tank in Chicago, found that while Chinese-educated AI researchers produced nearly one-third of all papers accepted at the NeurIPS conference, the leading AI research meeting in the world, most Chinese researchers study, live, and work in the United States. If they are forced to leave, such talent cannot be easily replaced.

If Joe Biden is elected president, his administration will no doubt reconsider some of these policies. Jake Sullivan, a Biden campaign advisor, recently said at an event at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (where I am a fellow) that there should be “less focus on trying to slow China down and more on running faster ourselves.” But whatever Biden does, the competition to determine international norms and standards for critical technologies will continue.

The geopolitics of repression

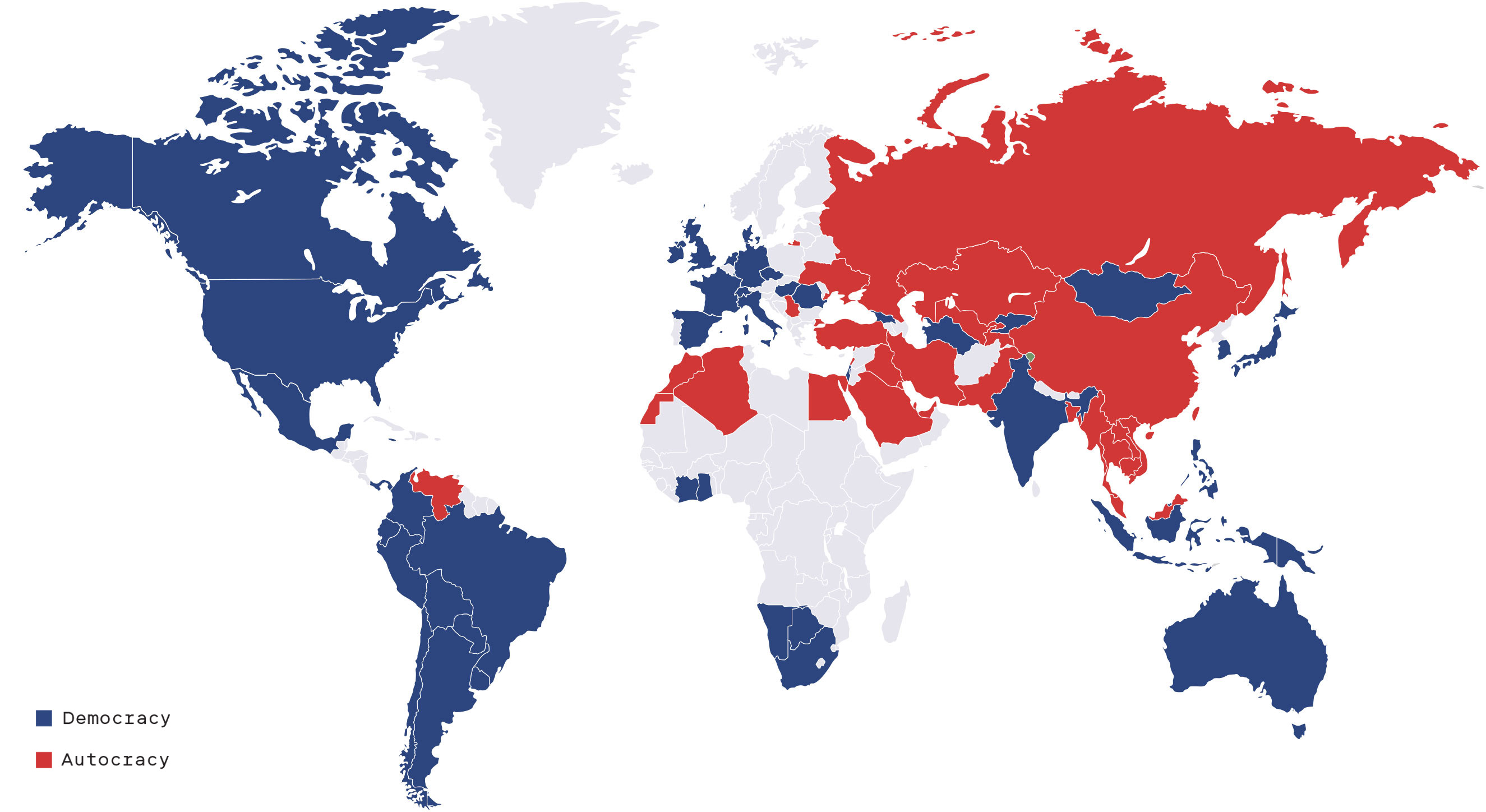

Other governments are also using technology to advance their political agendas. Even before the covid-19 crisis, the world was in the midst of an autocratic resurgence. Researchers from the Varieties of Democracy project estimate that 2.6 billion people, or 35% of the world’s population, are having their political liberties curtailed.

Authoritarians are using a raft of digital technologies to counter dissent, maintain political control, and stay in power. In my prior research and in an upcoming book, I document how cities in Kenya, Mexico, and Malaysia employ Chinese AI-powered technology to keep watch over citizens; how spyware from Israeli and US sources helps intelligence operatives in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt monitor dissent and track opposition figures; and how censorship and disinformation campaigns enable authorities in Thailand and Pakistan to tamp down criticism and flood digital channels with pro-government narratives.

Countries that possess public surveillance capabilities powered by big data and AI

Source: Carnegie Endowment

Autocratic regimes are far more likely to use these instruments for repression, but democracies sometimes use them to curb civil rights too. In the United States, for example, the advocacy group Freedom House observes, police have used technologies such as drones, facial recognition, and social-media surveillance in response to escalating Black Lives Matter protests.

The pandemic has accelerated this attrition of individual liberties. Data collected by Samuel Woodhams of Top10VPN, a digital privacy group, shows that as of July 2020, 50 countries had introduced contact tracing apps, 35 had adopted alternative digital tracking measures, 11 had implemented advanced physical surveillance technologies, and 18 had imposed censorship related to covid-19. Many of the countries using these techniques are democracies.

A big problem is that governments are rushing out health surveillance technology without proper vetting or oversight. Bahrain, Kuwait, and Norway all launched intrusive covid-19 tracing apps that “actively carry out live or near-live tracking of users’ locations by frequently uploading GPS coordinates to a central server,” Amnesty International reported in June. The report caused Norway to suspend its app’s rollout; Bahrain and Kuwait have not.

Of course, digital technology isn’t responsible for authoritarianism’s resurgence, but it gives crucial advantages to unsavory regimes. This illiberal assault is putting inordinate pressure on the liberal international order and the institutions that uphold it, including the UN, NATO, the World Health Organization, the World Trade Organization, and others.

China and Russia stand to gain the most from this. Indeed, some experts argue that they have directly pursued a “digital authoritarianism” strategy: providing powerful technology to help illiberal leaders entrench their regimes, thereby creating an autocratic alternative to the liberal international order.

Source: Michael Coppedge, ET AL. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.23696/VDEMDS20

My own research suggests that most of these regimes would pursue anti-democratic digital strategies even without Russia’s and China’s help. All the same, there is reason to worry about the growing global spread of Chinese technology such as Huawei 5G networks, Transsion mobile phones, and WeChat for e-commerce and communication. Not only does this increase global reliance on Chinese technology, thereby enhancing China’s influence, but many products, such as WeChat’s social app or Alipay Health Code (which classifies users’ health status and determines whether they are allowed to travel or enter certain public spaces), are designed to facilitate government surveillance and censorship. As Christopher Walker, Shanthi Kalathil, and Jessica Ludwig wrote this year in the Journal of Democracy, “The CCP [Chinese Communist Party] has been forging an increasingly seamless synthesis combining consumer convenience, surveillance, and censorship. This model is exemplified by such all-encompassing platforms as WeChat … which includes politically based content restrictions and lends itself to surveillance.” (See also the interview with Samantha Hoffman on page 56.)

Of course, technologies are often two-edged swords. Digital tools help civic movements, journalists, and political challengers. The ability of social-media networks to rapidly mobilize citizens and swell mass protests is a potent threat that no regime has fully neutralized.

It’s also worth remembering that while the US-China rivalry can dominate discussions about the future of technology, it’s not the only thing determining where trends are headed. The European Union, for example, is increasingly staking out its own independent policy positions. It’s emphasizing privacy, accountability for big tech firms, and transparency for big data and AI. India, Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria, and Indonesia are all deciding whether to try to carve out their own digital agendas or to act more as fence-sitters, playing China, the US, and the EU against one another.

Though commentators like Ian Bremmer of the Eurasia Group warn of a “great decoupling” between the US and China, with dire consequences for technology, talk of a new bipolar Cold War is overblown. There are too many new players and too many variables to assume that two superpowers will monopolize the rules of technology for the foreseeable future. Instead, we are likely to witness increased splintering as fresh ideas come to the fore, new platforms gain followings, and more people get online for the first time. A multipolar world with new, diverse sources of ideas, innovation, regulation, and geopolitical influence may not be such a bad thing at all.

Latest content

The coronavirus responders

A special series on coronavirus responses around the world.

Welcome to In Machines We Trust

A podcast about the automation of everything

Amid the covid-19 pandemic, shifting business priorities

Organizations are reshuffling projects and accelerating investments that were already underway, leaning heavily on technology to stay competitive.

Bottom right: it me.

-

-

How a $1 million plot to hack Tesla failed

A Tesla employee thwarted a ransomware attack that targeted the Gigafactory